Psychedelic Drug Helped People with Alcohol use Disorder Reduce Drinking, Study Shows (Today)

Psilocybin, the ingredient in magic mushrooms, along with talk therapy, showed significant benefit in the largest clinical trial of its kind.

Two doses of psilocybin pills, along with psychotherapy, helped people with alcohol use disorder reduce drinking for at least eight months after their first treatments, results from the largest clinical trial of its kind show.

“There’s really something going on here that has a lot of clinical potential if we can figure out how to harness it,” said Dr. Michael Bogenschutz, the director of the NYU Langone Center for Psychedelic Medicine at NYU Langone Health, who led what may be the first randomized, controlled trial of psilocybin for alcohol use disorder.

During the eight-month trial, 93 men and women ages 25 to 65 were chosen to receive either two psilocybin doses or antihistamine pills, which the researchers used as a placebo. They all also participated in 12 psychotherapy sessions.

All of the volunteers were averaging seven alcoholic drinks at a time before the trial.

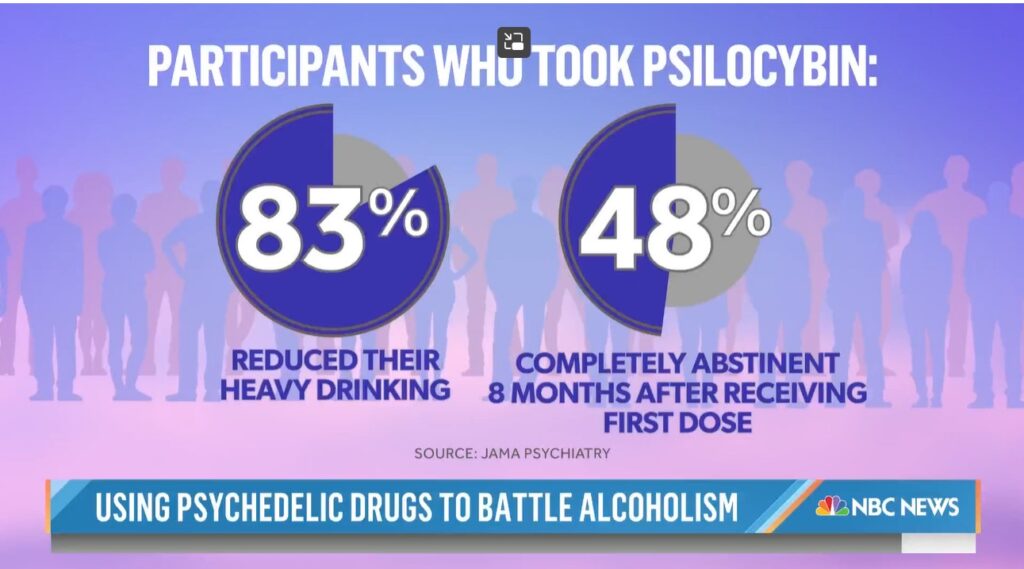

More than 80% of those who were given the psychedelic treatment had drastically reduced their drinking eight months after the study started, compared to just over 50% in the antihistamine control group, according to results published Wednesday in JAMA Psychiatry. At the end of the trial, half of those who received psilocybin had quit drinking altogether, compared to about one-quarter of those who were given the antihistamine.

NYU Langone Health led the trial, which began recruiting in 2014, with researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of New Mexico.

The new research is part of a global movement exploring whether psychedelic-assisted therapy — including therapy using ketamine and psilocybin, the active component in magic mushrooms — can be a more effective alternative to addiction and mental health treatments. Bogenschutz and his team specifically set out to test whether or not psilocybin, in addition to sessions of therapy, could cut cravings and help people with alcohol use disorder stay sober.

Earlier research from institutions around the world has indicated that psilocybin has the potential to treat a variety of addiction disorders, including alcohol use disorder, opioid use disorder and addiction to smoking.

“It’s really in line with accumulating evidence that psilocybin and other psychedelics that work in a very similar way in the brain can be effective in treating different types of addiction,” said Matthew Johnson, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, who wasn’t involved in the trial.

‘Magic Mushroom’ Psychedelic may Help Heavy Drinkers Quit (AP News)

The compound in psychedelic mushrooms helped heavy drinkers cut back or quit entirely in the most rigorous test of psilocybin for alcoholism.

Mary Beth Orr used to have five or six drinks every evening and more on weekends before she enrolled in a study in 2018 to see if the compound in psychedelic mushrooms could help heavy drinkers cut back or quit entirely. She stopped drinking entirely for two years, and now has an occasional glass of wine, and credits psilocybin for her progress.

More research is needed to see if the effect lasts and whether it works in a larger study. Many who took a dummy drug instead of psilocybin also succeeded in drinking less, likely because all study participants were highly motivated and received talk therapy.

Psilocybin, found in several species of mushrooms, can cause hours of vivid hallucinations. Indigenous people have used it in healing rituals and scientists are exploring whether it can ease depression or help longtime smokers quit. It’s illegal in the U.S., though Oregon and several cities have decriminalized it. Starting next year, Oregon will allow its supervised use by licensed facilitators.

The new research, published Wednesday in JAMA Psychiatry, is “the first modern, rigorous, controlled trial” of whether it can also help people struggling with alcohol, said Fred Barrett, a Johns Hopkins University neuroscientist who wasn’t involved in the study.

In the study, 93 patients took a capsule containing psilocybin or a dummy medicine, lay on a couch, their eyes covered, and listened to recorded music through headphones. They received two such sessions, one month apart, and 12 sessions of talk therapy.

During the eight months after their first dosing session, patients taking psilocybin did better than the other group, drinking heavily on about 1 in 10 days on average vs. about 1 in 4 days for the dummy pill group. Almost half who took psilocybin stopped drinking entirely compared with 24% of the control group.